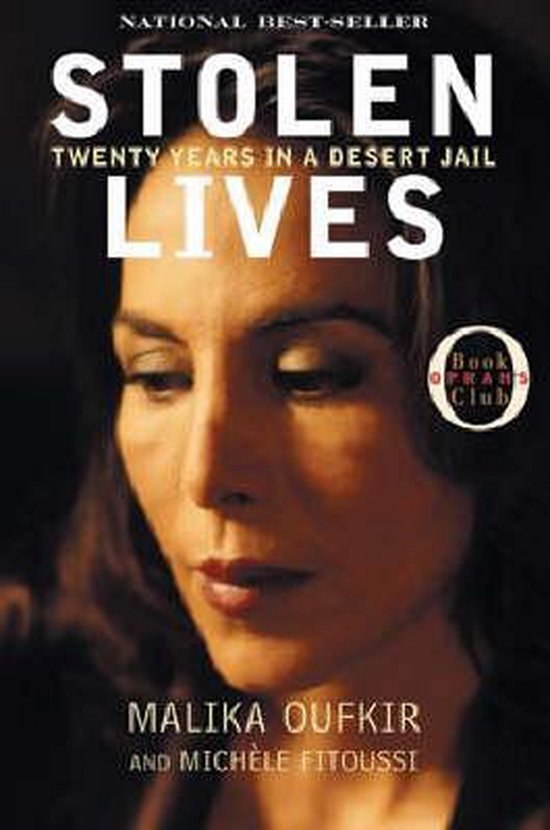

Stolen Lives

Introduction

style="font-style: italic"I was a princess in the court of the king.... Then he put me and my family in jail for 20 years.

Malika Oufkir tosses her fur coat onto the bed in her midtown Manhattan hotel room. She's elegant, slender, and quite beautiful, but, as she says, "I am not normal."

In truth, there is almost nothing normal about Oufkir. More than four years after she left Morocco, where she and her mother and brothers and sisters spent 20 years in prison, Oufkir still panics when she is out in the open. She craves quiet, dark rooms where she can be alone. New York frightens her. She hates crowds. She likes to eat alone, in silence.

"If I talk about it too much, think about it too much, I could become crazy or have a very violent reaction," Oufkir says of the time she spent in Bir-Jdid prison for a crime in which everyone knew she had taken no part. She was just 19 when her father, a powerful Moroccan general, led a failed coup against King Hassan II; the monarch immediately ordered General Oufkir's execution and banished his widow and six children, Malika, Myriam ("Mimi"), Maria, Soukaina, Raouf, and three-year-old Abdellatif, into internal exile.

Shuttled from prison to prison for five years, Oufkir and her family were eventually dispatched to Bir-Jdid, a prison barrack near Casablanca. Locked in separate cells around a central corridor, unable to see one another, Oufkir and her siblings spent their youth in Bir-Jdid, plagued by insects, vermin, and brutal deprivation.

"Hassan enjoyed keeping us in prison, starving us, freezing us, leaving us without beds or sheets or medical care. I think he took pleasure in it every day," Oufkir tells me, as if speaking of something that is both vaguely remote and entirely present. "He could have killed us. But he preferred to have us die slowly." Desperately—and miraculously—Oufkir and her family defied the fate Hassan intended for them when, using a spoon and a sardine can lid, they dug their way to freedom.

In heart-stopping and suspenseful portions of Stolen Lives, Oufkir's remarkable memoir, she recounts the days she and three of her siblings spent racing from embassy to embassy, attempting to gain political asylum after their escape from Bir-Jdid. The outcasts, now fugitives, faced unspeakable retribution if discovered. Hollow-faced, destitute, dressed in 15-year-old rags, they hitchhiked across Morocco, seeking help from former friends who, fearing the king, again and again turned them away. After five days on the lam, they succeeded in getting a hotel guest to phone Alain de Chalvron, a French radio reporter in Paris. "An incredible scoop," said de Chalvron, who alerted the French embassy to the Oufkirs' plight. Once their story was out, the condemnation of the international community made it impossible for Hassan to punish the family; Moroccan authorities nonetheless managed to keep them under house arrest for another three and a half years.

Even before her family's exile and escape, Oufkir led an extraordinary life. Born into an affluent and powerful family, she was chosen—at age five—by King Muhammad V to be a companion to his own small daughter, Princess Lalla Mina. The king moved Oufkir into a villa near the palace that she shared with his daughter. After three years Muhammad died, and his son Hassan II inherited the throne and guardianship of both Lalla Mina and Oufkir. Like his father, Hassan lavished attention and kindness on the girls and retained a strict German governess to ensure that they would be raised properly. Oufkir fondly recalls sitting around the piano, singing and dancing and otherwise enjoying good times with Lalla Mina and the new king.

Continues...

Copyright © by Zondervan

style="font-style: italic"I was a princess in the court of the king.... Then he put me and my family in jail for 20 years.

Malika Oufkir tosses her fur coat onto the bed in her midtown Manhattan hotel room. She's elegant, slender, and quite beautiful, but, as she says, "I am not normal."

In truth, there is almost nothing normal about Oufkir. More than four years after she left Morocco, where she and her mother and brothers and sisters spent 20 years in prison, Oufkir still panics when she is out in the open. She craves quiet, dark rooms where she can be alone. New York frightens her. She hates crowds. She likes to eat alone, in silence.

"If I talk about it too much, think about it too much, I could become crazy or have a very violent reaction," Oufkir says of the time she spent in Bir-Jdid prison for a crime in which everyone knew she had taken no part. She was just 19 when her father, a powerful Moroccan general, led a failed coup against King Hassan II; the monarch immediately ordered General Oufkir's execution and banished his widow and six children, Malika, Myriam ("Mimi"), Maria, Soukaina, Raouf, and three-year-old Abdellatif, into internal exile.

Shuttled from prison to prison for five years, Oufkir and her family were eventually dispatched to Bir-Jdid, a prison barrack near Casablanca. Locked in separate cells around a central corridor, unable to see one another, Oufkir and her siblings spent their youth in Bir-Jdid, plagued by insects, vermin, and brutal deprivation.

"Hassan enjoyed keeping us in prison, starving us, freezing us, leaving us without beds or sheets or medical care. I think he took pleasure in it every day," Oufkir tells me, as if speaking of something that is both vaguely remote and entirely present. "He could have killed us. But he preferred to have us die slowly." Desperately—and miraculously—Oufkir and her family defied the fate Hassan intended for them when, using a spoon and a sardine can lid, they dug their way to freedom.

In heart-stopping and suspenseful portions of Stolen Lives, Oufkir's remarkable memoir, she recounts the days she and three of her siblings spent racing from embassy to embassy, attempting to gain political asylum after their escape from Bir-Jdid. The outcasts, now fugitives, faced unspeakable retribution if discovered. Hollow-faced, destitute, dressed in 15-year-old rags, they hitchhiked across Morocco, seeking help from former friends who, fearing the king, again and again turned them away. After five days on the lam, they succeeded in getting a hotel guest to phone Alain de Chalvron, a French radio reporter in Paris. "An incredible scoop," said de Chalvron, who alerted the French embassy to the Oufkirs' plight. Once their story was out, the condemnation of the international community made it impossible for Hassan to punish the family; Moroccan authorities nonetheless managed to keep them under house arrest for another three and a half years.

Even before her family's exile and escape, Oufkir led an extraordinary life. Born into an affluent and powerful family, she was chosen—at age five—by King Muhammad V to be a companion to his own small daughter, Princess Lalla Mina. The king moved Oufkir into a villa near the palace that she shared with his daughter. After three years Muhammad died, and his son Hassan II inherited the throne and guardianship of both Lalla Mina and Oufkir. Like his father, Hassan lavished attention and kindness on the girls and retained a strict German governess to ensure that they would be raised properly. Oufkir fondly recalls sitting around the piano, singing and dancing and otherwise enjoying good times with Lalla Mina and the new king.

Continues...

Copyright © by Zondervan

| Auteur | | Malika Oufkir |

| Taal | | Engels |

| Type | | Paperback |

| Categorie | | Biografieën & Waargebeurd |