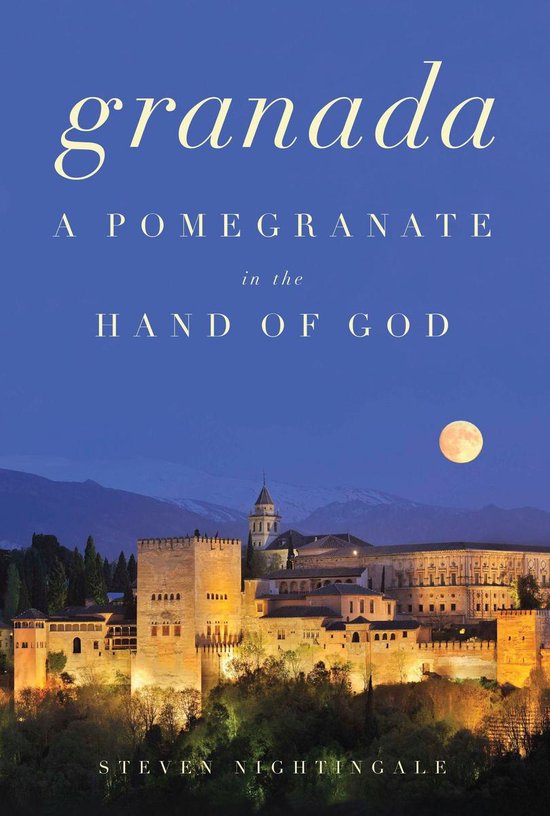

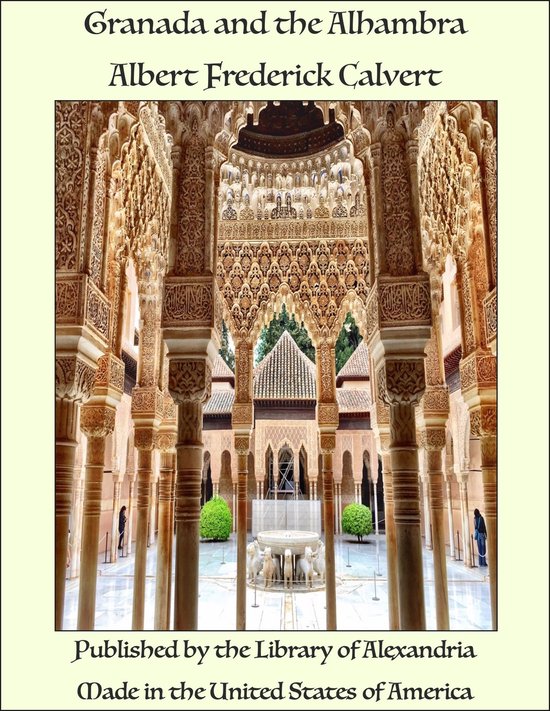

Granada and the Alhambra

Granada is the creation of the Moors. Its history is all of them—the record of their glory and their fall. The Pomegranate, as its conqueror styled it, ripened only in the warm sunshine of Islam, and withered with its decline. Under the Christian, it fell from the rank of a splendid capital to a poor provincial town. Now it subsists merely as a great monument to a vanished race and a dead civilisation. With Granada before it became the centre of an independent kingdom, we need concern ourselves but little. Its real interest dates from the establishment of the Nasrite dynasty in the first half of the thirteenth century. It was the time when the great Almohade Empire was breaking up. Probably all Andalusia would have shared the fate of Cordova and Seville, and the conquests of the Catholic kings been anticipated by two centuries, had not a young man of Arjona, Ibn Al Ahmar by name, determined to fashion for himself a kingdom out of the fragments of empire. With an ever-increasing following, he seized upon Jaen in 1232, and obtained possession of Granada itself in 1237. City after city opened its gates to him, including Malaga and Almeria, and in 1241 he was recognised as Lord and Sultan of all the territory between the Sierra Morena and the Pillars of Hercules, from Ronda to Baza. A great man, in every sense, was this founder of the Nasrite dynasty. His presence was fine and commanding, his manner bland and amiable, his courage worthy of the heroic age. For all his valour and prowess on the battlefield, no monarch prized peace more highly. He proved himself a true national hero and the father of his people. He fostered industry and agriculture, was a patron, like all his race, of arts and letters, and encouraged immigration by every means in his power. A far-sighted statesman, he perceived that a state so limited in area as his own could only hope to exist by virtue of an unusual density of population, and he offered every inducement to Muslims from the provinces conquered by the Christians to settle within his dominions. Granada was the last hope of Islam in Europe, and he resorted to all possible means to safeguard it. He concluded alliances with the rulers of Morocco, Tlemsen, and Tunis, and even of distant Baghdad. Above all, he neglected no means of humouring and conciliating the irresistible Castilian. He negotiated an alliance with Fernando III., binding himself to attend the Cortes (a curious stipulation for a Mohammedan) and to attend the king in his wars with 1500 lances. This latter part of the bargain he was speedily called upon to fulfil, and against his own co-religionists of Seville. It seemed an unnatural warfare, but, to palliate the iniquity, let it be said that Ibn Al Ahmar probably looked upon the Almohade citizens of Ishbiliah as heretics. At all events, whether his conscience approved his action or not, he contributed in no small measure to Fernando’s success, and was hailed enthusiastically as a conqueror upon his return to Granada. That the assistance he rendered was not looked upon as altogether voluntary by the people of Seville is shown by the fact that thousands of them migrated to his dominions and settled there.

| Auteur | | Albert Frederick Calvert |

| Taal | | Engels |

| Type | | E-book |

| Categorie | | Kunst & Fotografie |