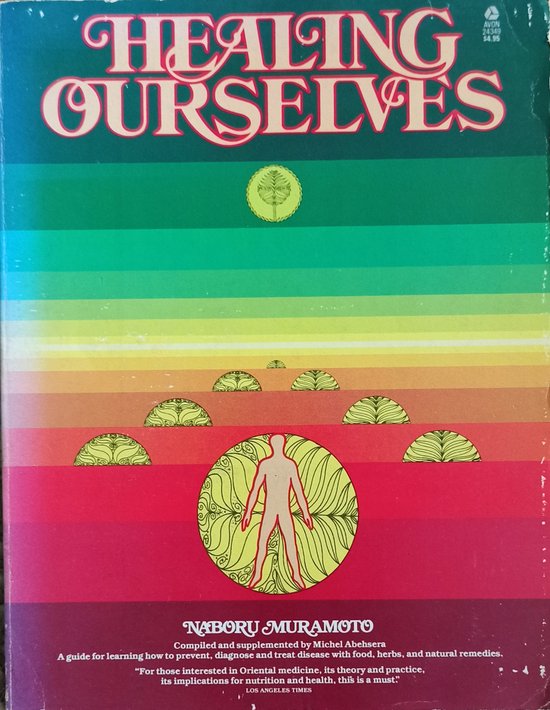

Healing Ourselves

It was neccesary that a book of this kind be written about Oriental medicine. Such a project required a genuine expert with vast practical experience, not a “tourist” who would travel to Japan or China, collect some concepts and data, and incorporate them into a book. We took our time—two years—until the right man presented himself.

Naboru Muramoto has been studying Oriental medicine for nearly thirty years. From personal experience we knew him to be skilled at both practicing and teaching it. When he arrived on the West Coast to speak there, we invited him to come to Binghamton to give a series of lectures. He accepted, and a month later he was here.

For four weeks he talked every morning to a steady crowd. Every word he said was written down. Each afternoon one or two editors studied with him privately to clarify each point and give it its proper place in the total perspective. All his answers were promptly recorded. At the end of the month, Mr. Muramoto ceased teaching the large daily classes and worked with the editors, reviewing all that had been said and correcting any possible misinterpretations. The editors, being well aware of the incompleteness of their understanding of Oriental medicine, were very careful to obtain clear answers, hoping to anticipate any difficulties that the reader might encounter.

After Mr. Muramoto left, a team of writers and editors was formed and the book began to take shape. We soon found that we would have to write an introduction for each chapter in order to smooth out che lectures and make of them an open garden where the reader could be at ease. We also found it necessary to weave in additional material to expand and connect the various ideas for the reader who was not fortunate enough to have heard the lectures “live,” In addition, several initial chapters had to be wricten to prepare the teader, since many of the Oriental concepts may be unfamiliar to him. Once the book was written, we sent one of the editors to San Francisco, where Mr. Muramoto is living, to check for errors and gather whatever information was necessary to fill in and complete the text. A sensitive and talented illustrator was needed also, one who would give the reader a feeling of ease and joy; for when pain strikes, warmth and understanding are needed to help heal it. As if by plan, we received a surprise visit from a young man who was eager to work for us. One look at a sample of his drawings and we were convinced that he was the right one for the job. Once the work on the content was finished, there remained the choice between a classical textbook form and a looser construction. We chose the latter in order to make the book accessible to laymen. What we at Swan House hoped to produce was a book of live teachings of Oriental medicine, as open and accessible as possible and directed to the needs of the people of the United States. Wherever you stand, whatever your beliefs and creed, you cannot fail to notice the dedicarion from which this book evolved. And if you come to see this, you are not far from believing in the practicality and efficacy of the | content of this book.

We LEARN to heal ourselves; it is our right. It is unnecessary to depend on others, however qualified. to do it for us. There are many ways to get rid of a cold besides simplistically taking pills which “work” for one day only. The cure must be complete. When we know how clogged our organs and arteries are, we have an insight into the extent of our freedom. If his body fuids do not run freely, how free can a man then be?

Perhaps che time is not too far off when most of us will be able to care for our health by ourselves, and do so simply, using what nature freely offers. It must be recognized that everyone is capable of curing himself. No miracles are involved. It is inspiring to realize that each of us can test how free he is by practicing his own medicine in a simple manner. Our present condition and mood, along wich our inherited constitution, point out the proper cure.

This book is not meant to cause a rapid and revolutonary change in the field of medicine and in the treatment of disease. It has been written so that everyone, whatever his orientation, can learn a simple, useful principle for everyday life, so that he will not panic over minor illness and rush to offer his body to the nearest doctor.

Oriental medicine has always taught that food is the best medicine. That is probably why traditional Eastern doctors did not expect to be paid; they believed that nature was doing the job, nor they. In fact, it is said that in the ancient Orient doctors’ salaries were suspended if their patients became worse, the doctor himself being held responsible for all expenses. It was agreed that the doctor’s job was to keep people well.

The Shurat, a three-thousand-year-old Chinese book, distinguishes five levels of doctors according to the type of medicine being practiced. The highest doctor is the Sage; he is followed by the food-doctor, the surgeon, the doctor of general medicine, and the animal doctor.

The most venerated doctor, the philosopher-doctor, teaches about the harmonious order of man and his world. The teachings of the food-doctor are classified as preventive medicine, which is known as the “medicine of longevity.” The surgeon employs his special skills to remedy the effects of violent injuries, also using herbs and food to help extend his patients lives. The doctor of general medicine uses herbs and employs the techniques of acupuncture, moxibation, and massage to cure specific ailments.

Oriental medicine operates on the principle of balancing Yin and Yang in all its remedies. This method based on subtlety and gradually changing balance is gentle, safe and long-lasting.

Modern medicine is preoccupied mainly with treating symptoms. Every year new sicknesses arise; every year a virus or a microbe makes the news. When a microbe is caught like a thief at che time of illness, it is immediately called “germ” and assumed to be the cause of the disease. The next step is to eliminate it wich surgery or drugs.

The Oriental approach is totally different. Nothing is destroyed out of fear, since the elimination of symptoms not only fails to help, but actually weakens the organism. À person with a healthy way of thinking does not try to separate himself from the world of bacteria. He knows that microbes and viruses too have their purpose and are beneficial to man. They are not our enemies, they are contained in our very life—in che food we eat and in che water we drink. And they cannot harm a person in good health. It is an ancient Oriental belief that disease destroys only those who deserve it. Science's anti-microbe actitude has developed as a result of modern man's inability to make himself stronger in body and mind.

Modern medicine is highly analytical. Its practitioners usually tend to reduce the body to its component parts. They try to isolate the disease to a single area and then concentrate on healing that specific part of the body. Thus, if there is pain in the stomach, most modern doctors will conclude that the stomach alone is sick. Sometimes they will “cure” the diseased area by removing it, as in the case of gastric ulcers. Gastric ulcers result from overeating and poor digestion. Removing organs is too simplistic an approach. To destroy something is not to cure ic. We cannot remove a part of our body without adversely affecting the whole.

Traditional Oriental medicine does not conceive of the body in parts; it considers the organ a part of the whole, and disease a deterioration of the entire bodysystem. Its highest practitioners reflect constantly upon the role of man in this world and the role of disease in this life. They know chat our bodies are inseparable from the soil chat feeds us. The earth, the plants it produces, the animals and mankind are all interrelared. Modern medicine says that the body consists of cells and that the cells themselves become diseased. This is a fine theory, but it remains for the Western doctor to realize that a disease in any part of the body always reflects a malfunctioning of the whole. Otherwise, too much time is spent in subdividing and classifying, a preoccupation which makes study unduly difficult. A Western doctor can spend eight years in medical school and emerge having mastered only the names of the parts of the body, the names of their diseases, and the names of the drugs to treat them. Based on its assumption that che body is an organic whole, Oriental medicine has names for only about one hundred types of diseases; the others simply fall into general categories. By realizing this unity, and by briefly studying the Yin-Yang principle, we can more easily learn che methods for healing ourselves.

There are several schools in Japan teaching traditional Oriental medicine. All recommend food as prevenrive medicine, but each has its own particular method of treating disease. We will not enumerate here the various forms of medicine being practiced in Japan and China today. While this would arouse the reader's wonder regarding the wide spectrum of healing techniques, it would leave him wich lirtle substance to work with, merely broadening his acquaintance with the world of medicine in a cursory and superficial way.

We thought we would best serve the reader’s interest | if we avoided directing his attention in too many directions

| Auteur | | Naboru Muramoto |

| Taal | | Engels |

| Type | | Paperback |

| Categorie | | Religie, Spiritualiteit & Filosofie |