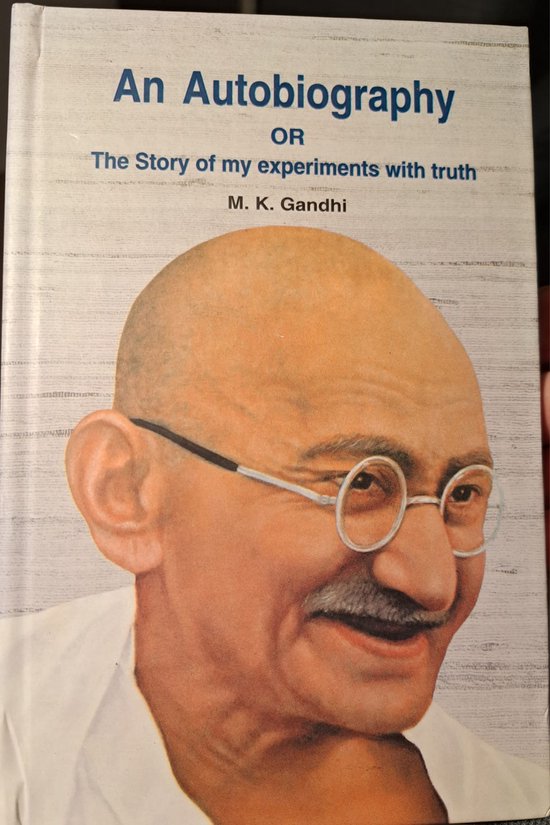

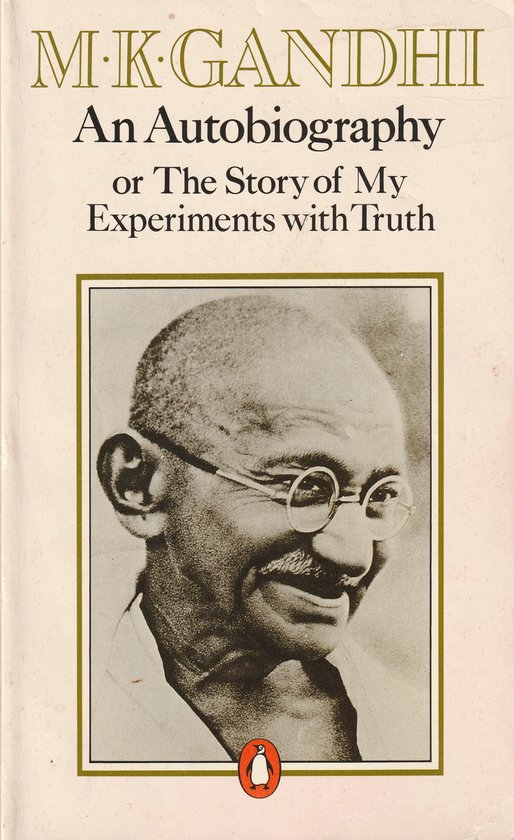

An autobiography, or, The story of my experiments with truth

I have nothing new to teach the world. ‘Truth and non-violence are as old as hills’ Mahatma Gandhi's aim in writing this autobiography was to give an account of his spiritual progress towards truth. Absolute ‘Truth is his sovereign principle and non-violence the method of pursuing it, In politics it meant freedom from foreign domination, within Hindu society it was the breaking down of barriers raised by caste and custom, in society it was living close to nature.

Written in 1925 under the title The Story of My Experiments with Truth, his work describes the practical application of his beliefs. T'he implementation of his doctrine, Gandhi believed, would result in a loose federation of village republics, freed forever from British control and influence.

Gandhi succeeded in uniting India in a national movement and did as much in the first half of the twentieth century as any other single individual to change the course of history.

‘His early life described vividly and meticulously’

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the great Indian political leader and soctal retormer, was born in 1869 at Porbandar in western India. In 1888 he went to London to study law, qualifying in 1891; there he is encountered with liberal and Christian ideas, and the teachings of Tolstoy. Returning to India, he practised law there until 1893 when he left to South Africa. His experience of racialism in South Africa led him to take up the rights of the Indian community and he soon emerged as their leader. He instituted a campaign of passive resistance in response to the Transvaal government’s discriminatory policy, coining the term Satvagraha — truth force — for this new revolutionary technique. This method of resistance was later used to great effect in India's struggle for independence. Gandhi returned to India in 1915 and in 1925 he became President of the Indian National Congress. His first major clash with the British government came in 1919 over the Rowlatt Acts, and he then introduced the hartal, a strike during which the people devoted themselves to prayer and fasting. However, when his olicies resulted í violence he abandoned the programme of mass civil disobedience. For a period Gandhì withdrew from politics and travelled throughout India preaching the cardinal tenets of Sis doctrine: Hindu-Moslem unity, the abolition of untouchability, and the promotion of hand-spinning. He adopted the peasant’s homespun cotton dhoti and shawl, a gesture which won the people’s hearts, and he became known as Mahatma — the great soul. During the struggle for independence he was imprisoned many times and this, together with his use ofthe hunger strike, adversely affected his health. In 1934 he resigned his leadership of the Congress, although he still remained a powerful influence; he resumed the leadership for a short tme in 1940/41 Gandhi continued to campaign against partition, which he saw as an unmitigated evil, until he realized its evitability. However, on Independence Day, 15 August 1947, he refused to celebrate and spent the day fasting and in prayer. He persevered in his work for unity and in 1948 in Delhi he undertook a fast to the death for peace between the two warring communities. But his pleadings for co-operation had aroused hostlity amongst the militant section of the Hindus and on 30 January 1948, one of them shot Gandhi dead.

There are many divergent views about Gandhi’s personality and his methods. Perhaps his most important contribution to India’s struggle for independence was his spiritual leadership, and his consequent influence over the mass of India's population. All his life he held to two fundamental principles, a belief in Ahimsa, or non-violence, and the concept of Satya, or truth; as he said: ‘My uniform experience has convinced me that there is no other God than'Fruth. And if every page o these chapters does not proclaim to the reader that the only means for the realization of Truth is Abimsa, [shall deem all my labour , . . to have been In vain.

Four or five years ago, at the instance of some of my nearest co-workers, l agreed to write my autobiography. I made the start, but scarcely had l turned over the first sheet when riots broke out in Bombay and the work remained at a standstill. Then followed 4 series of events which culminated in my imprisonment at Yeravda. Sjt Jeramdas, who was one of my fellow-prisoners there, asked me to put everything else on one side and finish writing the autobiography. l replied that 1 had already framed a programme of study for myself, and that Ì could not think of doing anything else until this course was complete. 1 should indeed have finished the autobiography had 1 gone through my full term of imprisonrment at Yeravda, for there was still a year left to complete the proposal, and as I have finished the history of Satyagraha in South Africa, l am tempted to undertake the autobiography for Navajivan. The Swami wanted me to write it separately for publication as a book. But 1 have no spare time. I could only write a chapter week by week. Something has to be written for Navajivan every week. Why should it not be the autobiography? The Swami agreed to the proposal, and here am Ì hard at work.

But a God-fearing friend had his doubts, which he shared with me on my day of silence. “What has set you on this adventure?’ he asked. “Writing an autobiography is a practice peculiar to the West. I know of nobody in the East having written one, except amongst those who have come under Western influence. And what will you write? Supposing you reject tomorrow the things you hold as principles today, or supposing you revise in the future your plans of today, is it not likely that the men who shape their conduct on the authority of your word, spoken or written, may be misled? Don’t you think it would be better not to write anything like an autobiography, at any rate just yet?’

This argument had some effect on me. But it is not my purpose to attempt a real autobiography. 1 simply want to tell the story of my numerous experiments with truth, and as my life consists of nothing but those experiments, it is true that the story will take the shape of an autobiography. But I shall not mind, if every page of speaks only of my experiments. 1 believe, or at any rate flatter myself with the belief, that a connected account of all these experiments will not be without benefit to the reader. My experiments in the political fields are now known, not only to India, but to a certain extent to the ‘civilized’ world. For me, they have not much value; and the title of ‘Mahatma’ that they have won for me has, therefore, even less. Often the title has deeply pained me; and there is not a moment I can recall when it may be said to have tickled me. But I should certainly like to narrate my experiments in the spiritual field which are known only to myself, and from which Il have derived such power as I possess for working in the political field. If the experiments are really spiritual, then there can be no room for self-praise. They can only add to my humility. The morel reflect and look back on the past, the more vividly do I feel my hmitattons.

What Il want to achieve — what I have been striving and pining to achieve these thirty years — is self-realization, to see God face to face, to attain moksha.* I live and move and have my being in pursuit of this goal. All that I do by way of speaking and writing, and all my ventures in the political field, are directed to this same end. Bur as I have all along believed that what is possible for one is possible for all, my experiments have not been conducted in the closet, but in the open; and I do not think that this fact detracts from their spiritual value. There are some things which are known only to oneself and one’s Maker. These are clearly incommunicable. The experiments I am about to relate are not such. But they are spiritual, or rather moral; for the essence of religion is morality. Only those matters of religion that can be comprehended as much by children as by older people will be included in this sro If 1 can narrate them in a dispassionate and humblesp te, … Laterally freedom from birth and death.

| Auteur | | M.K. Gandhi |

| Taal | | Engels |

| Type | | |

| Categorie | | Biografieën & Waargebeurd |